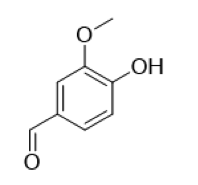

Vanillin

An Introduction to the Aromatic Compound

12.08.2020

Supervisors:

PD Dr. Jens Soentgen, Wissenschaftszentrum Umwelt (Universität Augsburg) und Prof. Dr. Christof Mauch, Rachel Carson Center (LMU)

Figure 1: Hi, I am vanillin, and this is my chemical structure.

Hi, my name is vanillin. You may have come across me – I am the primary aromatic compound of the vanilla bean. Every time you eat ice cream or vanilla yoghurt, it is me who creates this adorable flavour. So, since you are already reading this, let’s get to know each other better; I will tell you a little bit about myself. I am a natural aromatic compound. That means I can be extracted from natural sources, in my case the genus vanilla, belonging to the orchid family.

Figure 2: This is where I come from: the vanilla plant.

If you take the beans of this plant and dry them, they will unfold the typical aromatic flavour, and voila: here I am, spreading aroma to the world!

Figure 3: I particularly unfold during the drying of vanilla beans.

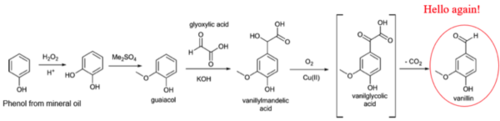

From there on, it is only a few steps into your hands. Can you already taste a cool vanilla yoghurt? Speaking of yoghurt – have you ever heard this urban legend, that they put wood shavings in the vanilla yoghurt, just to make it look like real vanilla beans have been used? It is not fully true but has a true point: You can technically modify lignin, a major component of wood, to gain vanillin molecules like me. That means, the wood shavings are not really put in the yoghurt, but my aroma is extracted from them instead of from real vanilla beans. I will be many times cheaper this way! Also, this process is environmentally friendly because it recycles waste from the timber and paper industry. Wow!

Figure 4: I can also be recycled from the lignin in paper waste.

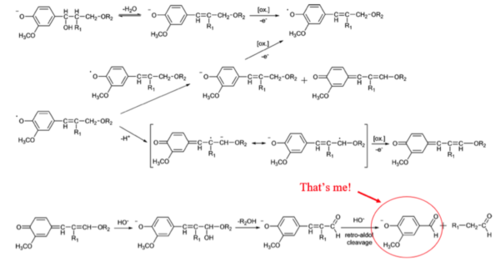

And even further – believe it or not – I can also be synthesized from mineral oil. That goes like this:

Figure 5: It is even easier to synthesize me from mineral oil.

Okay, I did not want to shock you with these chemical cascades, but the point is clear: Even though I am a natural substance, I can be produced synthetically. In this case, food legislation calls me “nature-identical aroma,” since the technical version of me is identical with my natural version. Ninety-nine percent of the vanilla flavouring used worldwide does not come from vanilla beans. The author of this final project believed this to be a very interesting topic. He wrote a small essay about me, or to be more precise, about nature-identical chemical substances in general. The term nature-identical has been used in the German aroma regulations 1981–2008 and, as mentioned, describes artificially produced aromatic compounds that are chemically equivalent to natural compounds. From an environmental studies point of view, this term is of great interest, because it touches the distinction between what-is-natural and what-is-artificial. It also touches a topic that is strongly present in the ecological discourse: the relation of chemicals to nature in general. How natural are chemicals? Rachel Carson had a lot to say about this topic. In Silent Spring she drew a strict line between natural and non-natural chemical substances: "The chemicals to which life is asked to make its adjustment are no longer merely the calcium and silica and copper and all the rest of the minerals washed out of the rocks and carried in rivers to the sea; they are the synthetic creations of man’s inventive mind, brewed in his laboratories and having no counterparts in nature." (Silent Spring, p. 8). For us, as environmental humanities scholars, it is certainly important to talk about this view that synthetic chemicals are unnatural since we usually spend our time with building bridges across the distinction between nature and its opposites (culture, technology, industry). We try to fill up the gap that seems to separate our lives from nature.

Nature-identical substances like vanillin that can be extracted from plants but can also be synthesized from mineral oil, do not really fit in the scheme of a nature-industry-antithesis. If you can artificially produce something naturally, the borders seem to tremble. A lot of research has been done on that, especially by philosopher Gernot Böhme, who wrote a book called "Naturally Nature: Nature in the Age of its Technical Reproducibility."

I quite liked the hint in the title, being a reference to Walter Benjamin’s essay "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction." Therefore, in my final project, I tried to add some thoughts on the topic of technically reproducing nature, with special concern for nature-identical chemicals like vanillin, together with an ecological reading of Benjamin’s reproduction theory.

If you want to know more about our little molecule vanillin, the (un)natural side of chemistry, or the idea of artificial nature in general, you can read the full essay in German here. Thanks!

Pictures:

1. Drawn by author

2. https://pixabay.com/de/photos/vanillebl%C3%BCte-vanille-wei%C3%9F-gelb-542019/

3. https://pixabay.com/de/photos/trocknen-vanilleschoten-mauritius-114135/

4. and 5. Drawn by author, according to Fache, Maxence, Bernard Boutevin and Sylvain Caillol. „Vanillin Production from Lignin and Its Use as a Renewable Chemical.” ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 4, no. 1 (2016): 35-46.

Downloads

- Schnurr_Final_Project_Naturidentisch (660 KByte)