Field Notes—Freising, 9 November 2024

09.11.2024

By Nil Özleyen, Environmental Studies Certificate Student, Rachel Carson Center LMU

An early foggy morning in Munich sets the mood for a fungus excursion and a short retreat in the countryside. On my way to the central station, I’m thinking of the last time I went on a field trip in eighth grade when we visited Çanakkale to see the memorial and the Trojan Horse. The excitement of embarking on a journey and seeing all of my friends and teachers outside the usual context was so exciting that it made me giddy the whole night before the trip. Now, as a master’s student preparing for a weekend in Freising, I feel the same anticipation.

Arriving at the historic town, our coordinator, Dr. Susanne Unger, waits for everyone to gather in the dining hall for coffee and introductions. Our group is an interesting mix of different disciplines–some with a political-sciences background, health, the natural sciences, and me, bringing the literary into the equation. I’m excited to see how fungi will link these perspectives.

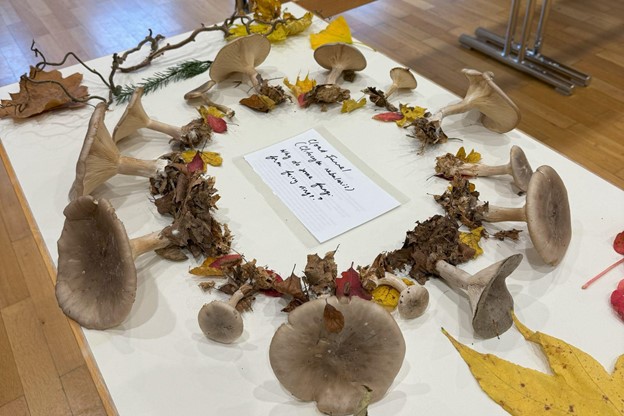

After our treats, we move upstairs to begin the first workshop of the stay. Walking into the large room, we’re greeted by an earthly, fresh scent. Our eyes widen as we see an abundance of mushrooms, branches, leaves, and moss with crawling ants and worms spread out on several tables. The day before, Dr. Alison Pouliot, a fungus expert, went into the woods and picked up all kinds of different fungi and other nonhuman entities to construct an isolated environment. This creates the perfect setting for us to discover how looking closely at fungi can shift how we perceive the world.

Gathered around the adorned tables, we can barely keep ourselves from exploring the display more closely. As if reading our eagerness, Dr. Pouliot prompts us to interact with everything as she gives us an introduction to the fungus kingdom and asks, “How does one find fungi?” The most straightforward answer seems to be to look for them in a forest. But I realize that, for me, spotting mushrooms has always been accidental. You don’t search for fungi, I think to myself, you just come across them. But to look for specific fungi, as we find out, you need more than luck. It involves practicing a series of naturalistic skills like understanding the symbiotic relationships between plants and fungi, and interpreting environmental cues such as moisture, light, and temperature.

Mushrooms on Display at Dr. Pouliot’s Workshop (Photo: Nil Özleyen, 2024)

Mushrooms on Display at Dr. Pouliot’s Workshop (Photo: Nil Özleyen, 2024)

What seemed like decorative shrubbery at first, reveals itself as a representation of the forest. The fruiting bodies of fungi emerge from the soil, tree barks, and leaves through a network of mycelium deeply entangled with all sorts of life above and below the soil that makes up the forest floor. Before we move on to the mushrooms on the desks, Dr. Pouliot draws our attention to the other entities and asks us if we can identify any of the trees based on their leaves. One of us picks up a browning leaf and says it’s from a maple tree. Someone else recognizes ivy and birch. One picks up the prickly dark green leaves of a pine tree. We learn that different fungi thrive in different environments. For example, the fungus you are looking for might only grow on and around birch trees making it crucial to be able to identify the tree before searching for the mushroom itself.

Next, we move on to a closer inspection of the mushrooms in front of us. Dr. Pouliot prompts us to touch the caps with our eyes closed and explain the sensation. We try to make sensory connections within our library of feelings but fall short of describing the specific feelings at the tip of our fingers. She encourages us to give descriptions—even if it sounds odd—in the hope that we can reach a collective understanding of the texture of these mushroom caps. After some tapping on the cap of my mushroom, I reach the conclusion that it feels exactly like the hollow wooden furniture you buy from Ikea. Then, a more bizarre description comes from across the room, as someone likens the texture to the gills of a blue crab.

“Why Do Some Fungi Form Fairy Rings?” at Dr. Pouliot’s Workshop (Photo: Nil Özleyen, 2024)

“Why Do Some Fungi Form Fairy Rings?” at Dr. Pouliot’s Workshop (Photo: Nil Özleyen, 2024)

We continue engaging with the mushrooms with other senses as we learn the proper way to smell them, which is by crushing their stipes, cupping them in our hands, and taking a few deep breaths with our eyes closed. With our dulled olfactory senses, we are less successful in making associations this time, only catching faint earthy and musky notes.

With our senses aroused, we layer up to go out into the forest for a hands-and-knees exploration of fungi in their natural habitat. Each one of us is tasked to give an excited squeak upon encountering a mushroom, and we all turn back into children, our gazes directed at the soil in search of nature’s eccentricities. Within the first few steps into the forest, someone spots an ink cap, and we all get down to take a closer look. Dr. Pouliot brushes her hands underneath the gills to reveal a dark spore print on her fingertips, which she casually wipes on her jeans as she explains this mushroom’s historical use as ink. She also adds an intriguing caveat: Although this mushroom is normally edible, consuming it with alcohol can make you very ill. When a curious inhabitant of the forest, a small mouse, emerges from under the foliage and approaches our circle around the mushroom, we get to think about the effects fungi have on other plants and animals, some being safe for them, yet toxic for humans.

Mushroom Foray in The Woods (Photo: Nil Özleyen, 2024)

Mushroom Foray in The Woods (Photo: Nil Özleyen, 2024)

Our group continues its way into the forest with everyone eager to spot a mushroom of their own. I notice that I begin to look more closely now—at cut tree trunks disintegrating from fungal enzymes, at the edges of fallen leaves, and beneath dense layers of foliage. With all of this previously hidden activity now revealed, the forest feels more alive than ever before.

Not long after, someone calls out and points to a rather dull-looking mushroom of a classic beige color and with a large cap. However, when Dr. Pouliot turns the mushroom upside down and as we pass along a portable binocular, we are amazed by its labyrinthine gills. Despite her vast experience, Dr. Pouliot doesn’t miss the chance to take a closer look and remark “Oh, isn’t that wonderful!”—further charging our curiosity.

We marvel at the variety of fungi we have encountered only within the first 10 minutes of our walk. From their eccentric aesthetics to their biological properties and role in human history, fungi reveal a world that can easily be overlooked. This diversity is key to ecological resilience and mirrors the need for diversity in the world: the need for varied ideas, perspectives, and connections to face challenges and adapt to change.

Shaggy Scalycap Mushroom (Photo: Nil Özleyen, 2024)

Shaggy Scalycap Mushroom (Photo: Nil Özleyen, 2024)

“Once you get fungally entangled,” Dr. Pouliot remarks, “you start seeing the whole world differently.” By the end of the weekend, her words resonate more profoundly. The fungi we observed weren’t just organisms—they were points of interconnection between a web of life that sustains all of us.